March 16, 2021

Documenting Destruction in Myanmar's Rakhine State With Openly Available Satellite Imagery

.jpg)

Max Bernhard

Myanmar has been thrown into turmoil after the military seized power and detained the country's democratically elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and other members of her government at the beginning of February. Dozens of people have been arrested during country-wide protests, and several have been killed.

Another conflict in the country has been going on since long before the February 1 coup, however. For decades, the Rohingya Muslim minority has been persecuted in the predominantly Buddhist country. More than one million of them have fled to neighboring states, such as Bangladesh, where the world’s largest refugee camp is located at Cox’s Bazar. Many of the Rohingya left Myanmar after deadly crackdowns by the military in 2016 and 2017 that have killed thousands.

Journalists, human-rights groups, and investigators have documented many of the atrocities that have occurred in Myanmar over the years. Still, there is no comprehensive database documenting the destruction of villages and homes in northern Rakhine State, where many of the Rohingya lived, in its entirety.

The Ocelli Project is trying to document this destruction in the most comprehensive way to date, using openly available satellite footage. Their goal is to document and categorize every single building that has been destroyed or burned, "whether it's a home, a market stall, or a school," says Benjamin Strick, the founder.

Strick is a Bellingcat contributor and digital investigator with a background in law, military, and technology. In the past, he has investigated bot networks, executions in Cameroon, as well as a massacre in Sudan, and drones in Libya. On his YouTube channel, he explains investigative techniques.

Strick initially researched the destruction in Myanmar in 2018 and 2019. He had done some work on identifying burned villages and wanted to see where else he could apply that methodology. "I went on Google Earth and started looking around the Rakhine State. And it was so obvious to see just how many villages [had been destroyed] and how large that scale was," he says.

The group then started working on the project earlier this year after noticing that there was no publicly available database documenting the destruction in Rakhine state in a comprehensive way. "We decided, let's take that initial research I did back in 2018, 2019, and do it properly, with a proper methodology, a deep focus on a six-month period, where we focus on every single square inch of the northern tip of the Rakhine State."

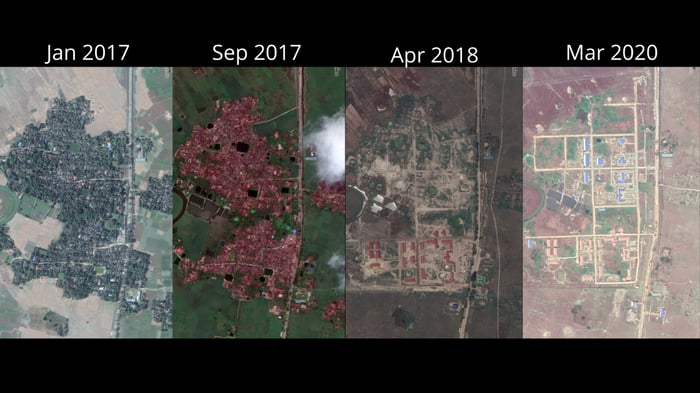

Destruction of a village in northern Rakhine State over time in satellite footage. - Credit: Ocelli Project / Google Earth

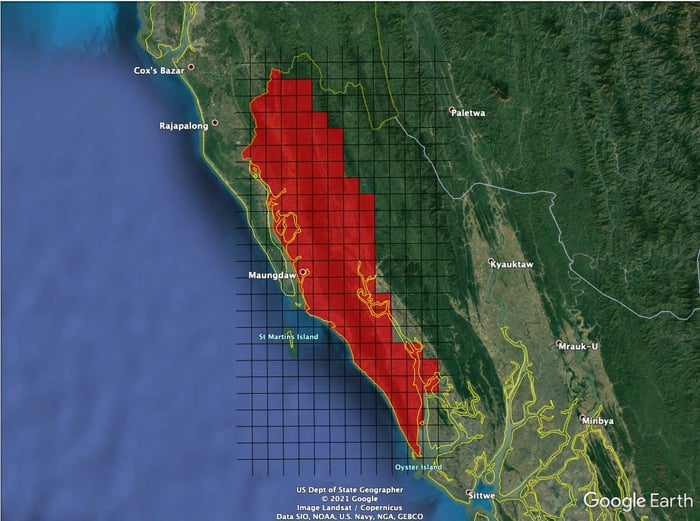

Before Strick and his teammates can reach that goal, they still have a lot of work to do. They are looking at an area of about 3,000 square kilometers, roughly for times the size of New York City. The group has divided that area up into 105 squares, measuring 30 square kilometers each. So far, they have completed about 20, and they are doing about one a day, Strick says. "It's a big project. But it's a good way of using that sort of by-hand documentation and curation of a map, to work to really get into the granular detail of everything in that square, and then move on to the next one."

Currently, the Ocelli Project's core team only consists of two people, Strick and Kayleigh de Ruiter. They also have help from about ten students at the University of London and other volunteers.

While the volunteers don't work on the project full time, Strick says he hopes with their help and a few more new additions to the team, they will be able to cut down the time to complete the project.

The area the Ocelli Project is investigating - Credit: Ocelli Project / Google Earth

Typically, once they have found evidence of a village being burned or destroyed, the researchers will use Google Earth and Sentinel Hub to then narrow down the time frame in which the incident took place. "We're hoping what we can do is say, you know, between this week, this village was burnt down," Strick says.

The way the researchers are scanning up and down the map is almost like the movement of a lawnmower, Strick says. "All we're doing, really, is sitting there with a mouse clicking on the history view of Google Earth in these little tiles going backward, forwards, backward, forwards. There's a change. Let's zoom in on the change. And let's verify it."

This approach is also where the project takes its name from. "Ocelli" refers to the lens of a dragonfly's eye, which allows them to detect change extremely fast. While human eyes perceive images at about 60 frames per second, it is about 200 frames per second for dragonflies. "We called it the Ocelli Project because what we're doing essentially is detecting change over time," Strick says.

Strick says the team has already identified two main dates where villages were destroyed. While the project isn't focusing on attribution, this finding "syncs in with some of the reports we've seen," he says. "It's almost two separate operations that have been conducted on those dates."

The destruction of a village, as documented on satellite footage. - Credit: Ocelli Project / Google Earth

In the end, Strick hopes to make the research as accessible as possible so that people unfamiliar with open-source investigations and analysis of satellite imagery can easily understand it. At the same time, he plans to also make the raw data and geographic markup, such as KML files, available, so researchers familiar with geospatial intelligence can access those as well. This is especially important for law enforcement and government investigators, who are required to replicate findings according to their own standards. "That's why we're not using commercial satellite imagery as well because we want this to be free, publicly available," he says.

Strick says with the project, he hopes to create a permanent record of what happened in Myanmar and that there will be more findings researchers, journalists, and investigators can use once the project is finished. "Maybe in 30 years' time, one of the kids that's in the Rohingya refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, now, might be at Oxford doing a Ph.D. in human rights research and might stumble across this database to make new findings as well. So that's kind of the purpose in the end," he says.

Your blog post content here…